FDA Final LDT Rule Could be Published Soon

FDA Final LDT Rule Could be Published Soon

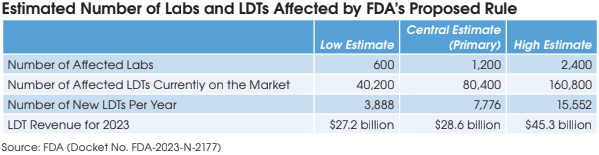

On March 1, the FDA submitted its final rule for LDT regulation to

the White House’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs

(OIRA). This is a perfunctory last step before the final rule is published

in the Federal Register. This could occur as soon as April 1. This will be

the most impactful new regulatory change for laboratories since PAMA

completely overhauled the Medicare CLFS in 2018.

FDA FINAL LDT RULE COULD BE PUBLISHED SOON

OIRA (pronounced “oh-eye-rah”) is a statutory part of the Office of Management and Budget within the Executive Office of the President. OIRA is responsible for reviewing all federal regulations (i.e., the Executive Branch’s administrative actions) to ensure they meet all statutory requirements. OIRA is currently headed by Richard Revesz, Administrator, who was appointed by President Biden and confirmed by the U.S. Senate in late 2022.

“OIRA reviewed the proposed rule in record time, so it is reasonable to expect that the review of the final rule will not be protracted. I would not be surprised if OIRA completes its review in 30 days and FDA publishes the final rule in the federal register in the first week of April,” according to attorney Sheila Walcoff, Chief Executive at the IVD consulting firm Goldbug Strategies (Gaithersburg, MD).

Typically, a final rule will specify an effective date of 30 or 60 days after the publication date, adds Walcoff.

Once a final rule is published it will be difficult to overturn.

Last Chance to Sway OIRA Against Regulation

OIRA staff held nine teleconferences with organizations advocating both for and against FDA LDT regulation last year. OIRA is next scheduled to meet with The Association for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine (ADLM — formerly AACC) on March 18. ADLM, which represents approximately 8,000 members, including clinical labs and IVD manufacturers, has steadfastly

opposed FDA regulation of LDTs. This could be the last chance that the lab industry has to sway OIRA against rubber-stamping the final rule.

Expected Legal Challenge

A final rule is almost guaranteed to trigger a lawsuit from lab trade groups, which will argue that the FDA does not have the authority to regulate LDTs.

The American Clinical Laboratory Assn. (ACLA — Washington, DC) seems to be gearing up for a lawsuit to the impending final rule. In a statement, ACLA President Susan Van Meter said:

ACLA has significant concerns about the legality and impact of FDA unilaterally imposing an ill-fitting medical device scheme on laboratory-developed testing services, which are professional services and not medical products. Should the agency promulgate a final rule, ACLA will assess its options at that time; but we continue to urge the agency to withdraw the proposed rule and reengage on advancing appropriate legislation.

Could a New Trump Administration Put the Kibosh on LDT Regulation?

As a component of OMB, OIRA is part of the Executive Office of the President and helps ensure that covered agencies’ rules reflect the President’s policies and priorities.

The FDA is moving quickly because the national election in November could result in a new administration opposed to LDT regulation. A new President could, immediately upon taking office, prevent a proposed rule from being finalized, according to long-time lab regulation expert Dennis

Weissman (Falls Church, VA).

However, Weissman says that changing or canceling a final rule is much more difficult. Once a federal rule has been finalized a new administration would be required to undergo the formal rulemaking process (i.e., opportunity for public comment on a proposal followed by final rule) to change or repeal all or part of a final rule.

In addition to this administrative action, Congress could also take legislative action to overturn a final rule, notes Weissman.